Recently I found myself deep inside Apple's MusicKitJS production code to isolate the user authentication flow for Apple Music.

Background

Over the past few months, I've made MoovinGroovin, a web service that creates playlists from the songs you listened to when working out with Strava turned on.

MoovinGroovin is integrated with Spotify, and I got a request from a user to add support for Apple Music.

As I looked into the integration with Apple Music, I found that to access a user's listening history, I needed a "Music User Token". This is an authentication token generated from an OAuth flow. Unfortunately, the only public way to generate these is through authenticating the () method of Apple's MusicKitJS SDK.

This meant I would have to handle authentication with Apple Music on front end, while all other integrations were handled by back end using passport.

And so, I decided to extract the auth flow out of MusicKitJS, and wrap it into a separate passport strategy (apple-music-passport).

This is where the journey begins...

TL;DR:

- Use beautifiers to clean up minified code.

- Understand how minifiers compress the execution (control) flow into

&&,||,,,;, and(x = y) - Recognize async constructs

- Recognize class constructs

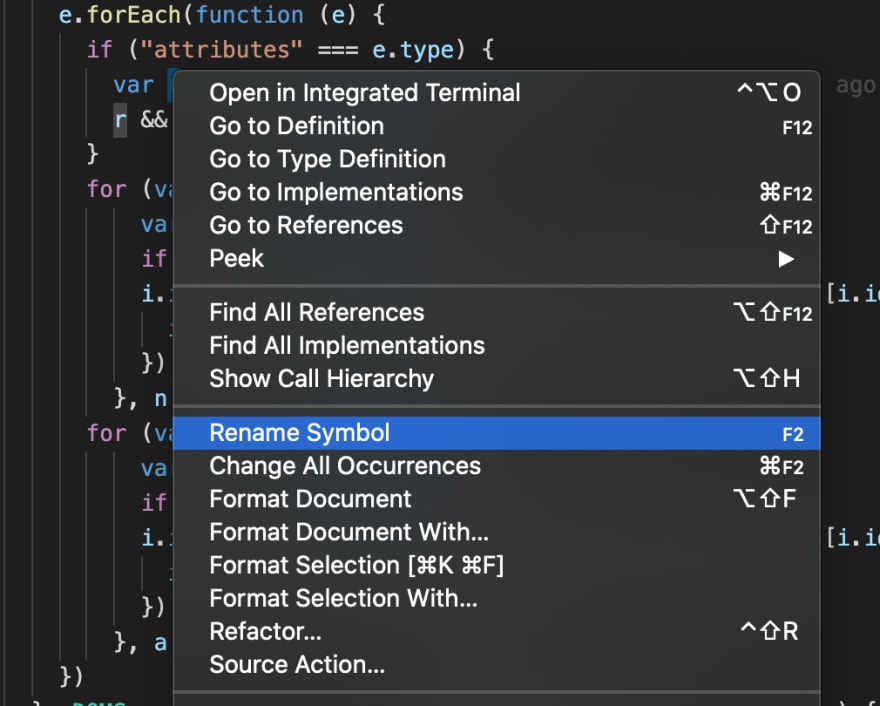

- Use VSCode's

rename symbolto rename variables without affecting other variables with the same name. - Use property names or class methods to understand the context.

- Use VSCode's type inference to understand the context.

1. Use beautifiers to clean up minified code.

There's plenty of these tools, just google for a beautifier/prettifier / deminifier / unminifier and you will find them. Beautify and Prettier VSCode extensions work just as well.

Most of these are not very powerful. They will add whitespace, but that's it. You will still need to deal with statements chained with ,, compressed control flow by && or ||, ugly classes and asyncs, and cryptic variable names. But you will quickly learn that - unless you're dealing with event-driven flow - you can just stick with where the debugger takes you and ignore most of the cryptic code.

There was one tool (can't find it) which attempted assigning human-readable names to the minified variables. At first this seemed cool, the truth is this will easily mislead you if the random names make somewhat sense. Instead, rolling with the minified variable names and renaming what YOU understand is the way to go.

2. Understand how minifiers compress the execution (control) flow into &&, ||, ,, ;, and (x = y)

As said above, you will still need to deal with cryptic statements like this:

void 0 === r && (r = ""), void 0 === i && (i = 14), void 0 === n && (n = window);

Let's break it down:

void 0 as undefined

void 0 === r

void 0 is undefined. So this checks if undefined === r. Simple as that.

Inlined assignment (x = y)

(r = "")

This assigns the value ("") to the variable (r) and returns the assigned value. Be conscious of this especially when you find it inside a boolean evaluation (&& or ||).

Consider example below, only the second line will be printed:

(r = "") && console.log('will not print');

(r = "abc") && console.log('will print');

Logically, this will be evaluated as:

"" && console.log('will not print');

"abc" && console.log('will print');

Which is:

false && console.log('will not print');

true && console.log('will print');

So while the second line will print, the first one will not.

Conditional execution with && and ||

The code above used && to execute the console.log.

Remember that JS supports short-circuit_evaluation. This means that right hand side of

abc && console.log('will print');

will ever be executed if and only if abc is truthy.

In other words, if we have

false && console.log('will not print');

true && console.log('will print');

Then console.log('will not print'); will never be reached.

And same, but opposite, applies to ||:

false || console.log('will print');

true || console.log('will not print');

What does this mean for us when reverse-engineering minified JS code? Often, you can substitute

abc && console.log('hello');

with more-readable

if (abc) {

console.log('hello');

}

One more thing here - be aware of the operator precedence.

Comma operator

So far, we understand that

void 0 === r && (r = "")

Really means

if (undefined === r) {

r = "";

}

We see, though, that in the original code, it's actually followed by a comma:

void 0 === r && (r = ""), void 0 === i && (i = 14), void 0 === n && (n = window);

This is the comma operator.

For our reverse-engineering purposes, it just means that each statement (separated by comma) will be evaluated and the value of last statement will be returned.

In other words, think of a chain of comma statements as a mini-function. And so, we can think the code above as:

(function() {

void 0 === r && (r = "");

void 0 === i && (i = 14);

return void 0 === n && (n = window);

})();

Overall, we can now read

void 0 === r && (r = ""), void 0 === i && (i = 14), void 0 === n && (n = window);

as

(function() {

if (r === undefined) {

r = "";

}

if (i === undefined) {

i = 14;

}

if (n === undefined) {

n = window;

return n;

} else {

return false;

}

})();

3. Recognize async constructs

Depending on the kind of code that you reverse-engineer, you may come into contact with async-heavy codebase. MusicKitJS was an example of this, as it handled requests to Apple Music API, so all methods that made requests were async.

You may find the async functions transpiled into an awaiter and generator functions. Example:

API.prototype.recommendations = function (e, t) {

return __awaiter(this, void 0, void 0, function () {

var r;

return __generator(this, function (i) {

switch (i.label) {

case 0:

return [4, this.collection(et.Personalized, "recommendations", e, t)];

case 1:

r = i.sent(), this._reindexRelationships(r, "recommendations");

try {

return [2, this._store.parse(r)]

} catch (e) {

return [2, Promise.reject(MKError.parseError(e))]

}

}

})

})

}

Sometimes the __awaiter and __generator names might not be there, and you will just see this pattern:

return a(this, void 0, void 0, function () {

return __generator(this, function (i) {

switch (i.label) {

case 0:

return ...

case 1:

return ...

...

}

})

})

Either way, these are async/await constructs from TypeScript. You can read more about them in this helpful post by Josh Goldberg.

The important part here is that if we have some like this:

return a(this, void 0, void 0, function () {

return __generator(this, function (i) {

switch (i.label) {

case 0:

/* ABC */

return [2, /* DEF */]

case 1:

/* GHI */

return [3, /* JKL */]

...

}

})

})

We can read most of the body inside case N as a regular code, and the second value of returned arrays (e.g. /* DEF */) as the awaited code.

In other words, the above would translated to

(async function(){

/* ABC */;

await /* DEF */;

/* GHI */;

await /* JKL */;

})()

4. Recognize class constructs

Similarly to the previous point, depending on the underlying codebase, you may come across a lot of class definitions.

Consider this example

API = function (e) {

function API(t, r, i, n, o, a) {

var s = e.call(this, t, r, n, a) || this;

return s.storefrontId = je.ID, s.enablePlayEquivalencies = !!globalConfig.features.equivalencies, s.resourceRelatives = {

artists: {

albums: {

include: "tracks"

},

playlists: {

include: "tracks"

},

songs: null

}

}, s._store = new LocalDataStore, i && (s.storefrontId = i), n && o && (s.userStorefrontId = o), s.library = new Library(t, r, n), s

}

return __extends(API, e), Object.defineProperty(API.prototype, "needsEquivalents", {

get: function () {

return this.userStorefrontId && this.userStorefrontId !== this.storefrontId

},

enumerable: !0,

configurable: !0

}), API.prototype.activity = function (e, t) {

return __awaiter(this, void 0, void 0, function () {

return __generator(this, function (r) {

return [2, this.resource(et.Catalog, "activities", e, t)]

})

})

}

Quite packed, isn't it? If you're familiar with the older syntax for class definition, it might not be anything new. Either way, let's break it down:

Constructor as function(...) {...}

Constructor is the function that is called to construct the instance object.

You will find these defined as plain functions (but always with function keyword).

In the above, this is the

function API(t, r, i, n, o, a) {

var s = e.call(this, t, r, n, a) || this;

return s.storefrontId = je.ID, s.enablePlayEquivalencies = !!globalConfig.features.equivalencies, s.resourceRelatives = {

artists: {

albums: {

include: "tracks"

},

playlists: {

include: "tracks"

},

songs: null

}

}, s._store = new LocalDataStore, i && (s.storefrontId = i), n && o && (s.userStorefrontId = o), s.library = new Library(t, r, n), s

}

which we can read as

class API {

constructor(t, r, i, n, o, a) {

...

}

}

Inheritance with __extends and x.call(this, ...) || this;

Similarly to __awaiter and __generator, also __extends is a TypeScript helper function. And similarly, the variable name __extends might not be retained.

However, when you see that:

1) The constructor definition is nested inside another function with some arg

API = function (e // This is the parent class) {

function API(t, r, i, n, o, a) {

...

}

...

}

2) That that unknown arg is called inside the constructor

API = function (e // This is the parent class) {

function API(t, r, i, n, o, a) {

var s = e.call(this, t, r, n, a) || this; // This is same as `super(t, r, n, a)`

...

}

...

}

3) That that same unknown arg is also passed to some function along with out class

return __extends(API, e) // This passes the prototype of `e` to `API`

Then you can read that as

class API extends e {

constructor(t, r, i, n, o, a) {

super(t, r, n, a);

...

}

}

Class methods and props with x.prototype.xyz = {...} or Object.defineProperty(x.prototype, 'xyz', {...}

These are self-explanatory, but let's go over them too.

Object.defineProperty can be used to defined a getter or setter methods:

Object.defineProperty(API.prototype, "needsEquivalents", {

get: function () {

return this.userStorefrontId && this.userStorefrontId !== this.storefrontId

},

enumerable: !0,

configurable: !0

})

is a getter method that can be read as

class API {

get needsEquivalents() {

return this.userStorefrontId && this.userStorefrontId !== this.storefrontId

}

}

Similarly, assignments to the prototype can be plain properties or methods. And so

API.prototype.activity = function (e, t) {

return __awaiter(this, void 0, void 0, function () {

return __generator(this, function (r) {

return [2, this.resource(et.Catalog, "activities", e, t)]

})

})

}

is the same as

class API {

async activity(e, t) {

return this.resource(et.Catalog, "activities", e, t);

}

}

- Use VSCode's

rename symbolto rename variables without affecting other variables with the same name.

When reverse-engineering minified JS code, it crucial you write comments and rename variables to "save" the knowledge you've learnt parsing through the code.

When you read

void 0 === r && (r = "")

and you realize "Aha, r is the username!"

It is very tempting to rename all instances of r to username. However, the variable r may be used also in different functions to mean different things.

Consider this code, where r is used twice to mean two different things

DOMSupport.prototype._mutationDidOccur = function (e) {

var t = this;

e.forEach(function (e) {

if ("attributes" === e.type) {

// Here, r is a value of some attribute

var r = t.elements[e.attributeName];

r && t.attach(e.target, r)

}

// Here, r is current index

for (var i = function (r) {

var i = e.addedNodes[r];

if (!i.id && !i.dataset) return "continue";

i.id && t.elements[i.id] && t.attach(i, t.elements[i.id]), t.identifiers.forEach(function (e) {

i.getAttribute(e) && t.attach(i, t.elements[e])

})

}, n = 0; n < e.addedNodes.length; ++n) i(n);

...

Identifying all rs that mean one thing would be mind-numbing. Luckily, VSCode has a rename symbol feature, which can identify which variables reference the one we care about, and rename only then:

6. Use property names or class methods to understand the context.

Let's go back to the previous point where we had

var r = t.elements[e.attributeName];

When you are trying to figure out the code, you can see we have a quick win here. We don't know what r was originally, but we see that it is probably an attribute or an element, based on the properties that were accessed.

If you rename these cryptic variables to human-readable formats as you go along, you will quickly build up an approximate understanding of what's going on.

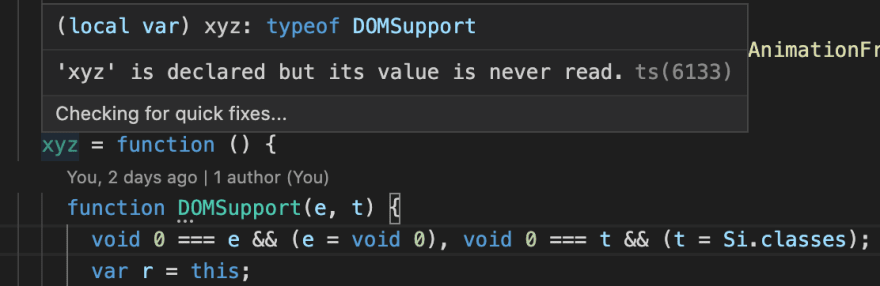

7. Use VSCode's type inference to understand the context.

Similarly to point 6. we can use VSCode's type inference to help us deciphering the variable names.

This is most applicable in case of classes, which have type of typeof ClassName. This tells us that that variable is the class constructor. It looks something like this:

From the type hint above we know we can rename xyz to DomSupport

DomSupport = function () {

function DOMSupport(e, t) {

void 0 === e && (e = void 0), void 0 === t && (t = Si.classes);

var r = this;

...

Conclusion

That's all I had. These should take you long way. Do you know of other tips? Ping me or add them in the comments!

Comments

Post a Comment